TAKOMA PARK, Md. — In retrospect, it might have been unwise for Pete Buttigieg to put a speedometer on President Joe Biden’s $5 billion plan to build electric vehicle charging stations.

“You’re going to see them sprouting up very quickly around the country,” the then-transportation secretary said four years ago in a Washington, D.C. suburb.

They did not sprout up quickly. And Donald Trump made sure everyone knew it. He gleefully seized on the plodding pace of the National Electric Vehicle Infrastructure program during the 2024 presidential campaign. In his acceptance speech at the Republican National Convention, he called the federal effort a “crazy electric Band-Aid” and a prime exhibit of Biden overreach and incompetence.

“They spent $9 billion on eight chargers,” he said, “three of which didn’t work.” The numbers were typical Trump exaggerations — in fact, at the time it was more like 15 stations. But he had hit on a glaring mismatch between Biden’s promise and what he delivered.

“My plan calls for 500,000 charging stations around the country so by 2030 we’re all electric vehicles,” Biden said in the summer of 2019, while still vying for the Democratic nomination. As president, he made the 500,000-charger pledge a centerpiece of his infrastructure push, promising to “build a national network” to be created by the government and private sector. When he got the bipartisan infrastructure bill passed in November 2021, it included $5 billion for the NEVI program, with its primary goal of building a safety net of EV charging stations along America’s highways.

But when the election rolled around three years later, NEVI appeared to have accomplished little. A built-out federal network would have included thousands of charging plazas, but Biden had opened only 25 locations by the time he left office. (Buttigieg declined comment for this story. A spokesperson for Biden did not respond to a request for comment.)

Biden created the impression that federal efforts would yield swift results. But he also handed NEVI a heavy rucksack of secondary goals — like boosting union labor standards and competing with China — and let it loose into a maze of federal and state bureaucracy that drastically slowed construction.

But there’s more to it. Despite the obvious failures, NEVI is, in a sense, succeeding.

Beyond the raw number of chargers they wanted to build, Biden’s people had an overriding goal: to take the glitchy, frustrating experience of EV charging and transform it into a smooth operation that could supersize across the nation’s highways. To do that, they sought to establish a common set of rules and requirements that would spur the many actors of the charging world to coordinate so that all drivers — not just Tesla owners — could count on a charging experience that, well, works.

By that goal, NEVI is working.

Biden didn’t get to campaign on the success of shiny new chargers at highway exits. But by insisting that EV drivers get the same plug-in and payment experience regardless of where they go, his administration did lay the groundwork for the EV revolution of tomorrow — even if he won’t get credit for it.

NEVI “forced the entire industry to raise its game around reliability, redundancy and performance that will be remembered as an important legacy,” said Nick Nigro, the founder of Atlas Public Policy, which studies the EV charging network.

It’s a political failure that morphed into a policy success. This curious path holds intriguing lessons for a Democratic Party that just won a series of promising elections and is contemplating how to govern on its next turn in power.

Within the party, there’s a debate over the so-called “abundance” agenda offered by liberal journalists Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson in their much-talk-about book. Their thesis, in a nutshell, is that Democrats admirably care about all sorts of things — but that often prevents them from getting results on anything. They can’t build high-speed rail in California, for example, because they need years of environmental studies and community-impact statements. If they want to win, abundance-advocates say, Democrats need to cut the red tape and stick a shovel in the ground.

NEVI in particular became a target of the abundance crowd. On comedian Jon Stewart’s podcast, Klein bemoaned the fact that, despite billions of dollars passed for EV chargers, “by the end of the administration, they just have not happened.” For Klein, the question facing Democrats is whether they can shake off their affinity for bureaucracy and persuade the American people that they can actually get things done — and NEVI is a clear example of their failure to do so.

But it’s not quite so simple. In fact, NEVI has endured where so many other Biden policies have met their end in the Trump administration in part because of the bureaucratic arcana that made it a political loser.

On Inauguration Day, Trump announced that he would freeze NEVI, as he did with a host of programs dear to Democrats. But it turns out that Congress had written out the program in such specific detail — and had thrust it so deeply into Washington’s core spending programs — that Trump had little room to flout the legislative branch. NEVI not only survived a court challenge but was reluctantly adopted by the administration. While Trump has relaxed some of its most burdensome requirements, the core mission of constructing a federal charging network has endured, shielded by pages upon pages of Democratic legalisms and technicalities. In other words, NEVI survived because it was the wonky if ungainly child of bureaucracy that Democrats are so good at creating.

That has Democrats wondering what lessons NEVI and its near-death journey hold for their next president. Is a long-term win worth it if it doesn’t help you hold on to power? How does a government re-learn to build fast when the laws go slow?

“Maybe we should have been clearer early on about the metrics of success,” said David Turk, a top aide who managed the program for the Energy Department. “Maybe we focused too much on substance, and we should have thought of the political liability of not enough federal chargers.”

Jeremy Symons, a longtime Washington climate adviser, thinks of it in the context of Trump’s wholesale attack on everything Biden had built. “If you only have four years to build before things get torn down, you have to ask fundamentally different questions. What can get implemented quickly enough to matter?”

As it happens, the place where Buttigieg made his fateful forecast of NEVI is a perfect example of how government and industry have failed to deliver a good charging experience.

RS Automotive sits at a high-traffic intersection just blocks from the Washington, D.C. border, in the ultra-blue suburb of Takoma Park. In 2019, it got stirring media coverage as the first American gas station to rip out its pumps and go all-electric.

But since then, the buzz has waned.

In June, I arrived at RS Automotive to meet David Moon, the Democratic majority leader of the Maryland State Assembly. He showed up in his first all-electric ride, a black Kia EV.

Moon got interested in EV policy when he took a road trip to Florida with his wife. Like so many others, he was dismayed by how many highway chargers simply didn’t work. It was, he said, “really eye opening.”

When he got back home to Maryland, he drove around to see what electric stations were available, especially in more remote areas like Western Maryland and the Eastern Shore. Within an hour’s drive from Washington, he found that most hotels, even the new ones, didn’t have a charger on site. The cities frequented by EV-driving tourists had few stations, and many were broken.

“Our state was nowhere near … the charging infrastructure to sustain the lofty policy goals we had installed elsewhere,” he told me.

Those goals are mostly about climate change, a threat that concerns many of Moon’s constituents. Cars and trucks are one of the largest sources of carbon emissions contributing to climate change, and scientists predict that, as the atmosphere warms and glaciers melt, rising sea levels will one day inundate Maryland’s Chesapeake Bay shoreline.

For a decade now, the threats of climate change have led Maryland and other liberal states to subsidize charging stations. These unglamorous plug points are a weak spot in any EV transition. Charging stations are necessary to give potential EV buyers confidence that they can energize their vehicles on the go. But since they are at first little-used and generate low revenue, it’s been hard for station builders to thrive while they wait for more customers. Governments have tried to propel charging stations across this valley of death by covering all or part of a station’s construction costs.

The biggest recipient of such aid in Maryland is the Electric Vehicle Institute (EV Institute), which operates the charging station at RS Automotive that Moon and I were about to use. Between 2015 and 2022, this home-grown Maryland EV-charging company received almost $6.3 million of aid from the Maryland Energy Administration, which runs several programs to subsidize charging stations, according to a tally by E&E News. In all, state money bankrolled more than 300 EV Institute locations. That includes $958,000 that in 2017 helped construct fast chargers at two state-owned rest stops, Maryland House and Chesapeake House, that capture the traffic on Interstate 95 — the highway backbone between New York and Washington.

Today, those chargers along I-95 are leaving drivers frustrated. On review sites, users say that EV Institute’s chargers are often down. When they do work, they provide only 50 kilowatts of power, which could take more than an hour to charge a modern EV.

“Please boot these clowns outta here and install some modern charging infrastructure, MD!” a user named Adam posted this summer on Plugshare, an EV-charger review site. On a reporter’s visit to Maryland House this summer, one of EV Institute’s six stations was broken. None allowed for payment by smartphone app, since EV Institute has no app.

This experience is common at publicly funded charging stations across the country. Most charging stations funded by government grants haven’t been required to keep up to date with new technology — or even to keep functioning.

Back at the RS Automotive site, Moon and I were having little luck. Several cars were able to charge, but not mine. I plugged one connector into my rented Ford Mustang Mach-E, and then another. Neither of them worked, and there were no attendants around to ask for help.

Moon remembered a different EV Institute charger on a curb nearby. When we pulled up, we found it covered with graffiti, a piece of paper taped to its screen that said OUT OF ORDER. Moon apologized profusely and pointed me to another EV Institute charger at Takoma Park’s city hall. I futzed with each of the cables. Each box eventually delivered the screen message CHARGING FAILED. Moon shook his head.

“It’s a wild thing, how this is so typical,” he said. “Prime locations are being occupied by non-functioning charging.”

I would have liked to ask Matthew Wade, the EV Institute’s top executive, about these problems — but he didn’t reply to interview requests. More ominously, the customer-support phone number posted at every station is now disconnected. When I interviewed Wade two years ago at RS Automotive, my notes gave one reason the stations are so glitchy: They are difficult to repair. Wade told me that when an irate customer reports a failed session, the reason isn’t obvious. The culprit could be the hardware, the software, even the credit-card reader. Technicians with the skills to rebuild a high-voltage charging station were so rare that Wade had to fly them in from California.

“It’s far more complicated than just replacing some charging,” Wade said at the time.

The mediocre sessions at EV Institute’s stations on I-95 have a stark counterpoint. Just steps away are banks of Supercharger stations run by Tesla, the country’s leading EV automaker. The Tesla network is the country’s largest and fastest growing, but it isn’t everywhere, and is closed to most non-Tesla EVs on the road today. Unlike other EV owners, Tesla drivers can easily pay for sessions using an app, and chargers deliver 150 kilowatts in ideal conditions — three times as much as EV Institute’s. Users report they are almost always working.

Bringing Tesla-like efficiency to the country’s EV-charging system is what Andrew Wishnia had in mind in 2021 when he wrote the rules for what turned out to be NEVI.

As a senior policy adviser to the U.S. Senate’s Environment and Public Works Committee, Wishnia drafted the climate-transportation portion of the bipartisan infrastructure law, one of Biden’s first big legislative accomplishments. Previously, he had been a climate adviser in the Obama White House, where he handled an effort to convert the nation’s 600,000-vehicle fleet to electric.

“Why can’t we do the same thing for our national highway system?” he asked.

The idea was to use federal money to form a backbone of charging stations along major highways. Chargers are proliferating in cities, where most EV drivers live, and are steadily starting to appear in more far-flung locations. But many gaps still exist on the rural stretches that make up the great American road trip. Charging providers avoid those lonely places because the customers are few.

Enter NEVI: The government would focus “on building where the private sector wouldn’t,” said Andrew Rogers, an official at the Federal Highway Administration who oversaw the program’s implementation.

That goal was concrete, easily understandable. But behind it stood a second one, harder for the public to grasp.

America’s artisanal EV charging system — calling it a ‘network’ is a stretch — had no national standards. Take Maryland as an example: EV Institute’s chargers were struggling because the company had to figure out big, systemic problems on its own. It couldn’t find repair workers because such workers barely existed, and few new recruits were on the horizon because no nationally recognized curriculum existed to train them. No payment system connected EV Institute’s chargers to other networks. Charging sessions often failed because the software and hardware that connected the car, the charger and the electric grid didn’t converse fluently; no industry-wide protocols gave them a common language.

“It was the wild, wild West,” said Loren McDonald, an independent analyst who studies the charging network. “No one was holding the industry accountable.”

Meanwhile, one part of the U.S. charging system was demonstrating the possible. Tesla’s Supercharger network was fast and reliable — but closed to non-Teslas.

The chance to tap funds from the bipartisan infrastructure law, in fact, is part of what spurred CEO Elon Musk to open Tesla chargers to others, and led to one of NEVI’s most wrenching mid-course corrections. In mid-2023, automakers stampeded to adopt Tesla’s charging standard, known as NACS, and that threw NEVI’s rules into confusion. While NEVI doesn’t require NACS, many non-Tesla EV drivers can now use Tesla’s network.

NEVI would use the lure of $5 billion from the federal government to spur other players to collectively achieve the same performance. It would bind the motley, disjointed parts of the EV ecosystem — its dozens of providers, its Frankenstein mix of hardware and software — into an interoperable whole. Operators could get billions of dollars of free money, but first, everyone would have to agree to certain rules.

Lots of rules.

In Abundance, Klein and Thompson made the argument that Democrats can’t get things done because, over the decades, they have developed a knee-jerk belief that solutions lie in the elaborate machinery of government. As Thompson put it, they spend “too much time thinking about process and too little time thinking about outcomes.”

The outcome of NEVI — the part the public was supposed see — is easy enough to understand: a station every 50 miles along major highways, and no more than a mile from an offramp. They would work with any model of EV. Each location would have four dispensers, with minimum power of 150 kilowatts — three times faster than EV Institute’s stations in Maryland. In the end, America’s drivers would have an electric safety net that anyone could rely on.

But underneath that straightforward vision was a second aim that the public barely knew about: Wishnia’s ambition to remake the ramshackle system into an efficient, unified network. And that would involve a lot of process.

How would the government provide its $5 billion? The fast way would have been grants. But that risked the government creating yet another wave of orphaned and poorly maintained stations, like EV Institute’s. Instead, the infrastructure law took a different — but much slower — course.

The dollars would flow through the Federal-aid Highway Program, the big and lazy Mississippi River of federal transportation dollars. Uncle Sam bankrolls roughly a quarter of road and bridge work along 3.9 million miles of state and federal highways. The funds are doled out to state departments of transportation, which decide how to oversee the work according to their particular rules.

Wishnia said this was strategic: The feds would lend a guiding hand whilethe states got flexibility. Taxpayer dollars wouldn’t repeat the mistakes of the past. For example, Wishnia’s bill insisted that stations operate for at least five years. The vigil would be kept by state DOTs, which, after all, have kept the federal highway system running for nearly 70 years.

“We wanted EV charging infrastructure to be an integrated part of the broader transportation system,” Wishnia said. After all, this was the same funding formula that created the interstate highway system in the 1950s. He added, “It really had to go to state departments of transportation, so they had skin in the game.”

But there was a problem: State DOTs knew next to nothing about EV charging stations. The federal government would fill that gap too, by trying something never attempted in the republic’s two centuries. Every agency in the U.S. government is run by a single federal department. Congress would break that precedent by creating a new unit with two parents.

An electric vehicle is two things. One is transportation, which is a complex system. The other is electricity, which is a complex system of a very different kind — one that until recently has not provided power for millions of vehicles. So Congress created the Joint Office of Energy and Transportation, or JOET. The Transportation Department would oversee the funding. The Energy Department, with its bench of experts at the national labs, would provide the electrical expertise.

But Wishnia left one rule out: a deadline for states to finish the job. And that would prove politically disastrous for the Biden administration.

Gabe Klein, the founding executive director of JOET, remembers a meeting he had with the White House soon after he took his job in late 2022. He was worried about expectations.

“Nobody seemed to understand the timeline to build heavy infrastructure like DC fast chargers,” he told me. (Fast chargers, like those on highways, use DC, or direct current.) As for NEVI’s timeline, he told the White House, “We’re going to see sort of the pinnacle of chargers going in, we hope, 2027, ’28” — long after the end of Biden’s first term.

Klein saw that NEVI had taken something already time-consuming — the building of a fast-charging station — and baked it into an intricate bureaucratic layer cake.

The process started with the states. Knowing the amount of money they would get, they had to submit to the Federal Highway Administration a detailed annual plan

Those plans then needed federal review, which was completed in late 2022. With plans in hand, states were free to get started — or at least to start getting started. States typically plan for big projects in stages. It’s a slow process that in this case would be even slower. That’s because building an EV charging station is utterly unlike what DOTs usually do.

“We’re good at building roads, we’re good at building bridges, we’re good at maintenance and things like that,” said Lyle McMillan, a technology director with the Utah Department of Transportation, at a meeting of state officials last year in Detroit. With NEVI, he said, “We’ve been basically tasked with creating a new product, a new something, and doing it on the fly — and still meeting 2,000 different rules that are in place to do it.”

The first weird thing for state DOTs to wrap their heads around was that the stations were located not on the highway, but off it, on private land they didn’t control. No one even knew what land it would be. First the DOT or its private partners had to find a “site host” that met the feds’ strict rule of being no more than a mile from the highway — think of a restaurant or gas station. But to complicate things, these retail outlets often had no skills or interest in building or operating the charger itself. That would fall to a third entity, the charging provider.

These sites would need a startling 600 kilowatts of power to charge cars quickly — far more than what is often available on the roadside. New and stronger wires needed to be built by the electric utility — an entity that can rival a state DOT for its ponderous, bureaucratic ways.

Industry veterans know that standing up an EV charging plaza is so complex that it often takes 18 months. Even Tesla, the industry leader, can take two years. And a special circumstance made the timeline even longer: The snarled supply chains during the recovery from the pandemic meant that getting an electrical transformer, key to supplying the station’s power, could take three years.

It all would have been challenging enough without the stacks of rules that vexed McMillan of the Utah DOT.

He referred to Title 23, the 818-page regulatory bible that dictates how states can spend federal transportation dollars — and overlays with other federal rules and regulations that Congress passed in bygone eras.

For example, companies doing the work must meet minimum wage rules created in the 1930s to yank the country out of the Great Depression. Another Depression-era proviso requires contractors to audit their financial statements and post bonds to ensure their work. And don’t forget the National Environmental Policy Act, passed in the smog-filled year of 1969, that includes lengthy checklists to ensure a project causes minimum harm to land, water and air.

These rules, though burdensome, are a well-worn groove for the handful of engineering firms and general contractors that are big and deep-pocketed enough to build a highway or bridge. But none of this describes the motley scrum of companies that approached states hoping to build the NEVI charging stations. They were mostly startups with short histories and unaudited books.

The charging industry was as frustrated as McMillan and his DOT peers. In addition to navigating the regulatory mazes of Title 23, they found that every state had its own unique practices for digesting federal dollars.

“You’re starting over every time in learning a state’s procurement process,” said Andrew Dick, a business development manager at Electrify America, one of the country’s largest charging networks.

“The industry general perception is that they were in over their heads, moving too slowly, and requiring things that didn’t need to be required,” said one charging-company official granted anonymity to speak candidly about industry-related matters.

As states and industry swam through the molasses of Title 23, they had an urgent question for the federal government: What are the details of this new and improved network you want us to build?

Those details would form a second set of slowing agents, in part because the answers wandered beyond NEVI’s infrastructure mandate and into a controversy between union labor and climate advocates. New rules would only deepen the quicksand builders needed to trudge through — until the White House realized, too late, that it hadn’t delivered the charging network that America expected.

Every federal NEVI guideline would benefit or inconvenience someone. The referee would be JOET, charged with creating a network that would be both cutting-edge and reasonable.

But JOET presented a different kind of obstacle to the quick progress Biden promised for NEVI: It was so brand-new that it barely existed. Klein, a former head of transportation departments in Chicago and Washington, wasn’t hired until almost a year after the infrastructure law passed. Dick, of Electrify America, described JOET’s ascent as “building the plane as you fly it.”

Bureaucratic infighting was inevitable. JOET and its experts sat in the Department of Energy. But the states’ marching orders came from the Federal Highway Administration, part of the Department of Transportation. State officials interviewed for this story gave JOET high marks for its expertise but said FHWA’s management of charging-station dollars was slow and inconsistent.

By early 2023, JOET had its final rules ready. In a 35,000-word document, it explained how software and hardware systems would interoperate, harmonized pricing and payment systems, and set standards for cybersecurity and reliability.

But the NEVI guidance didn’t stop there. It rippled out to farther shores, aiming to use the momentum of a new industry to create the sort of country that Biden’s big domestic agenda sought to build. It instructed states to “‘remove barriers for disadvantaged communities” and to “support good-paying, union jobs.”

Two key Biden constituencies — labor and climate — found their goals in conflict. Organized labor wanted jobs; the climate lobby wanted charging stations rolled out quickly to spur EV adoption.

The International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers union scored a win when the White House decreed that the electrical workers building stations would have to receive apprenticeship training. That meant higher-quality — but slower — growth in the workforce.

And, just as everyone got the government’s final guidance, the Biden administration threw a curveball.

Charging stations were the first genuinely new equipment on federal highways in decades. That invited a role for ‘Build America, Buy America,’ a program dating from the 1930s that dictates the domestic content of infrastructure that gets federal aid. The White House declared a high bar for EV charging gear: 55 percent needed to be made in America. The move would spur domestic manufacturing, please Biden’s union base and box out tech from China.

There was just one problem: Hardly any American factories capable of producing EV chargers existed.

By early 2023, a year and a half after the bill was passed, the NEVI program had become a maelstrom of process, with little in the way of outcomes. The 2024 election was heating up, and officials had only a handful of EV-station openings to celebrate.

Jonathan Levy, the former chief commercial officer at EVgo, a provider of charging stations, remembers going to the White House to meet with Biden’s infrastructure team and asking, “Do you want ribbons cut or not? Because at the pace you’re going, nothing is going to get cut.”

It was a deficiency that Klein, at the Joint Office, knew too well. He was getting an earful from states and industry about how hard it was to meet the labyrinth challenges of Title 23.

“We were constantly kicking everybody in the ass, escalating things to the secretaries and deputies at the White House,” he said. “We were sounding alarms that things weren’t going well.”

In late 2023, POLITICO was the first media outlet to note that NEVI had not opened a single charging station. Other media picked up on the story, and by June, Trump started putting criticism of NEVI into rotation at his rallies, suggesting that the program’s slow pace called Biden’s competence into question. It also boiled up in Congress, where Sen. Jeff Merkley (D-Ore.), a Biden ally, labeled NEVI a “vast administrative failure.”

The White House at last realized it had a crisis in the making. Administration officials started hitting the phones, pleading for speed.

“Because it was in the press so often, it had higher visibility, so we were pushing our cabinet members and governors pretty hard,” said Samantha Silverberg, a top Biden infrastructure adviser.

States’ progress on NEVI did not follow a neat red-blue divide. Ohio, a Republican-led state, was the fastest to open stations, as the administration of Gov. Mike DeWine made it a high priority. Other red states moved slowly, if at all: Wyoming flatly refused to build stations in its big empty spaces, while Florida’s governor, then-presidential candidate Ron DeSantis, proudly did nothing with the NEVI money. His transportation secretary, Jared Purdue, said that Biden’s EV plans “politicize the nation’s transportation infrastructure.”

The deep-blue states of Washington and Oregon were standing still, and other blue states were slogging. But the White House had little leverage. As it turns out, handing decision-making power to the states to get their buy-in had a downside. “The control is almost entirely in the hands of the states,” said Silverberg, and they “were not under the gun to spend that money quickly.”

The White House did prod Maryland, which like most states didn’t open a single NEVI station during Biden’s term. Joe McAndrew, the state’s assistant transportation secretary, said the state barely budged on the program under former Republican Gov. Larry Hogan. The governor’s attitude on NEVI, McAndrew said, was, “if we never spend the dollars, can we just give it back?” (Hogan said through a spokesperson that his administration worked hard to get the infrastructure law passed and “followed all procedures in the law.”) Under Gov. Wes Moore, a Democrat who took office in 2023, NEVI plans started moving.

When Washington asked for speed, however, even Maryland had to shrug. It was wending through the many rules that slow down any federal transportation project, like approvals through the National Environmental Protection Act. To name one example, Maryland had to demonstrate that its stations’ lights, meant for user safety, didn’t shine into any nearby forests.

“We unfortunately were not in position,” McAndrew said, “that we could accelerate to meet any type of November schedule.”

Last summer, nine months after defeating Biden in the presidential election and six months after freezing the NEVI program, the Trump administration did something rare: Itrelented, re-opening the funding spigots and reluctantly making the program its own, while relaxing some of the Biden-era rules.

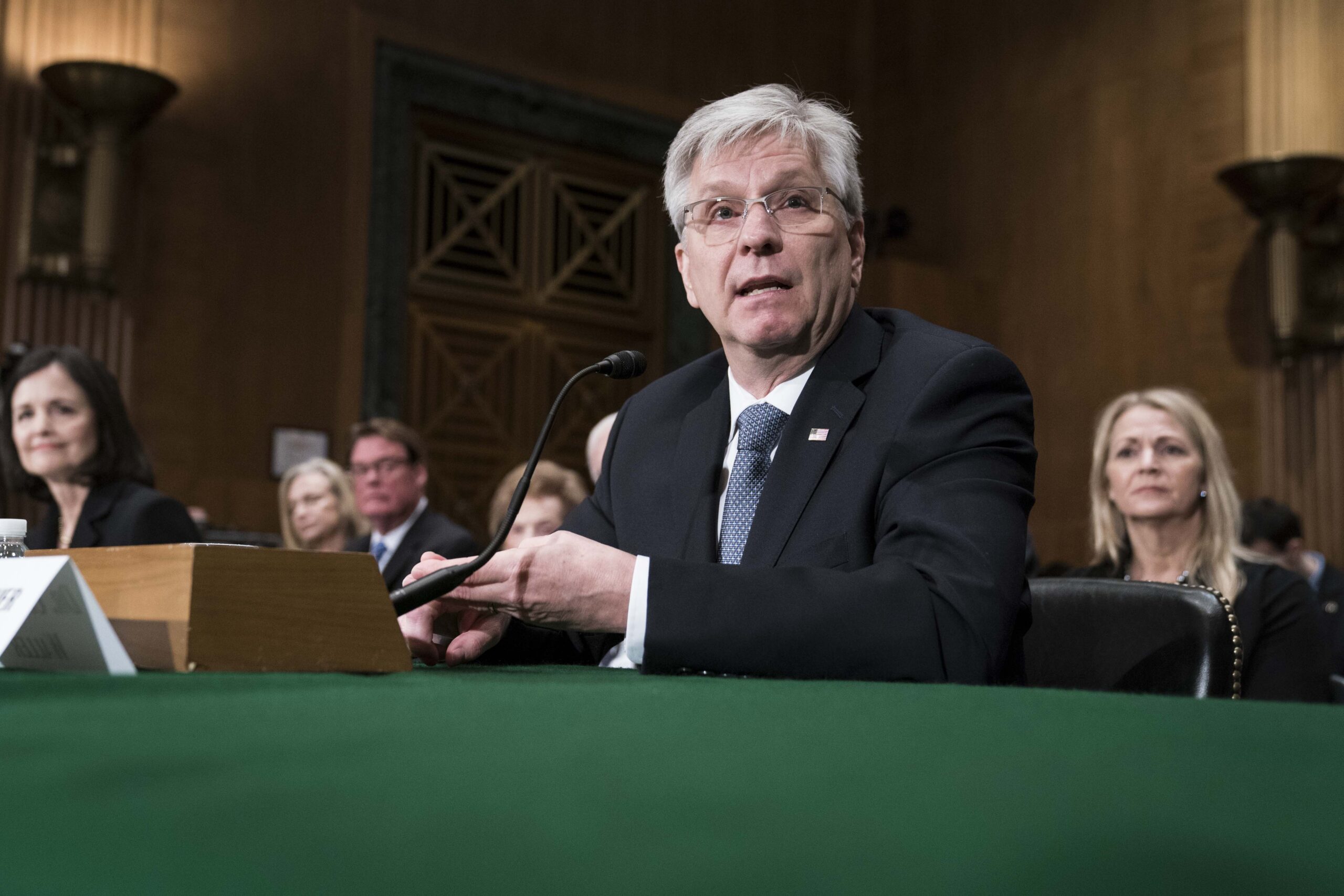

“While I don’t agree with subsidizing green energy, we will respect Congress’ will and make sure this program uses federal resources efficiently,” said Sean Duffy, Trump’s transportation secretary.

Duffy threw out the Biden administration’s 35,000 words of NEVI guidance and replaced them with a brief, 2,500-word document “to allow states to actually build EV chargers.” Gone was the dictum to build stations every 50 miles. States, not the feds, would declare when their charging network is finished. Money could be used to charge not just cars, but big trucks, too.

Some EV advocates who typically criticized the Trump administration found themselves praising it. They were relieved, not just that the administration’s long NEVI freeze was over, but that a looser regime could get NEVI moving. “We appreciate the Department’s efforts to streamline the program,” said the Electrification Coalition, a nonprofit that promotes EVs.

Even Wishnia, the author of NEVI, said he approved of Trump relaxing some of the voluminous guidance that the Biden administration had written.

“We’re now in a position where we can give states more latitude,” he said.

After a torturous birth under Biden and a near-death experience under Trump, NEVI is starting to hit its stride.

State departments of transportation have wrapped their heads around charging infrastructure; money is flowing, and stations are under construction. Analysts expect that thousands of NEVI-funded chargers may be online, as JOET director Klein predicted, by 2027 or 2028. In Maryland, DOT officials say the first wave of 22 stations will be online by this time next year.

NEVI runs out of funding next year, and it’s unknown if the next big transportation bill will include money for EV charging. But whether it does or not, NEVI’s less publicized goal — that of spurring a well-functioning charging system with common standards — is becoming a commercial reality.

In Maryland, at least four large charging plazas are under construction near highways. None rely on federal aid. The scale of new, privately funded stations makes NEVI’s footprint seem quaint. They have more ports and refill batteries faster. Stations are being used more frequently, and reliability is improving. An October study by Paren, an EV-charging consultancy, projected that the U.S. will open almost 17,000 fast-charging ports this year.

“They’re not waiting for NEVI,” said Lanny Hartmann, a charging advocate in Maryland “They’re just going to build them.”

Despite their initial resistance to NEVI’s rules, some industry leaders now credit it for bringing them together.

“It’s overlooked as a success of the program how broadly it became adopted as standard industry practice,” said Dick, of Electrify America. He noted that states and utilities now regularly adopt federal rules, like the size and reliability metrics, as their own. It created “a level of consistency and cohesion that didn’t exist before,” he said.

With NEVI, Democrats failed loudly — but succeeded quietly. It’s a conundrum to chew on.

No Democratic strategist interviewed for this story had a clear roadmap for how to retain the labor and environmental protections built over a century while also building infrastructure fast. NEVI shows that it’s not straightforward; the government can get it right even when it seems at first to get it wrong. But with the midterms and the next presidential contest coming, the party still has to learn how to get out of its own way.

“We need to take a hard look at state capacity and trusting them with public infrastructure,” reflected Rogers, the FHWA official who carried out much of NEVI. “They have to have the flexibility to deliver 21st-century projects without putting it through a 20th-century machine.”