In June 2017, India’s Central Bureau of Investigation raided the offices of the owners of NDTV: one of the country’s most prominent news channels. NDTV, investigators declared, had defrauded a bank by failing to repay its loans. The bank released a statement saying the station had paid back its obligations years earlier. But that did not stop the government from going after the company, or lobbing additional accusations of money laundering and tax evasion. The government demanded that the channel immediately hand over nearly $50 million.

When I first read about this, I was on a plane, enroute to New Delhi. It was August 2017, and I was about to start working there as a journalist. I had a vague understanding of what I was getting myself into: since coming to power in 2014, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi had overseen a notorious crackdown on his country’s civil society. But I wanted to master the details before landing, and so I had downloaded almost every article I could find about the assault on Indian democracy.

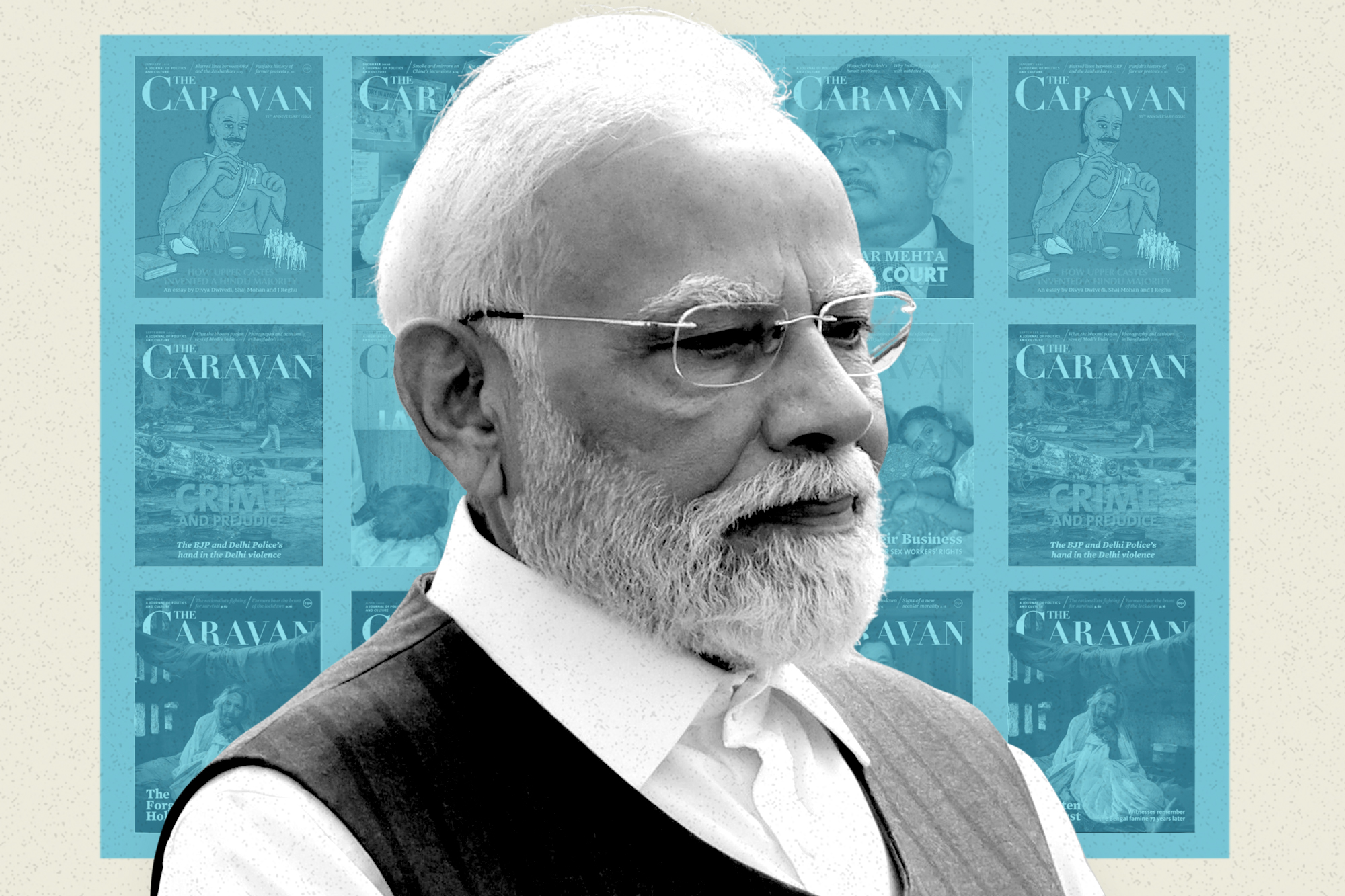

The attack on NDTV was particularly alarming to me. I wasn’t going to work for the station, but I was about to work for The Caravan — an outlet known for being even more critical of Modi. The magazine was less than 10 years old, but it had already earned a reputation for its hard-hitting investigations into India’s political, business and religious elites. That reputation was exactly why I wanted to work there. In fact, it was the whole reason I was going to New Delhi. Yet it also meant the publication could easily be targeted by authorities.

“Don’t get arrested,” my dad told me, before I left for my flight from New York City. I laughed, but he wasn’t kidding. “Seriously,” he said.

Spoiler alert: I never found myself in jeopardy. But what I saw over the course of my year there, and what my colleagues have experienced since, has made me deeply worried about the fate of journalism in my own country. Since returning to office in January, U.S. President Donald Trump has worked aggressively to muzzle the press, and his techniques for doing so closely resemble those of Modi. Both the Trump administration and Modi’s team sue their critics with reckless abandon. Both governments cut the media off from taxpayer resources. Most concerningly, both use their investigatory powers to bludgeon critics.

The biggest difference is that it’s happening faster here. “We’re a long film, and you’re the montage,” said Seema Chishti, the editor in chief of The Wire, another independent Indian outlet. “We’re watching it happen very quickly and saying, ‘Oh god, this is all so familiar.’”

In India, the crackdown has been effective: the country’s mainstream media now rarely critiques Modi. In the United States, the press is also starting to pull some of its punches. But if India’s trajectory is cause for alarm, it also provides some reason for hope. Despite over a decade of attacks, the country still has a small but mighty free press. It includes The Caravan, The Wire and a collection of other youngish outlets. They have survived through a combination of luck, determination and ingenuity. They have, for example, teamed up to cover stories and support each other when under assault. They have inspired journalists who are still committed to independent reporting, despite the difficulties. Above all, they have learned how to make money in ways that the Indian government struggles to obstruct. As a result, it has been hard for state officials to bring them down.

As American journalists contemplate life under an illiberal government, they would thus do well to study these places. They provide a template for how independent media can survive — and even fight back — when staring down autocracy.

As a brand, The Caravan has existed for nearly a century. The magazine was first established in 1940, and helped push for Indian independence. But that iteration closed in 1988, before being resurrected 21 years later, in 2009. At the time, India’s independent media scene was growing, but the country lacked a good outlet for long-form reporting and essays. The Caravan’s revivers hoped to provide one.

The magazine came back at an auspicious time for Indian democracy. The country’s then-prime minister, Manmohan Singh, was a mild-mannered, center-left technocrat, not a populist or a demagogue. He repealed a national security law that made it easy to clamp down on critics. Activists blasted him for both his economic and social policies. Journalists published damning investigations into his deputies. But he never responded with real hostility.

In 2013, however, India’s political environment began to grow more restrictive. “There were changes in newsrooms,” Vinod Jose, the first executive editor of the new iteration of The Caravan — and my former boss — told me. Editors unsympathetic to India’s right-wing were pushed out. Newspapers began limiting their critical coverage of Hindu nationalists. This was because, over the course of that year, almost everyone realized that the Hindu-nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party was going to win the next elections. And the BJP’s leader — Modi, then the leader of the Indian state of Gujarat — was not known for his embrace of open society. Modi rarely granted interviews to journalists. When reporters tried to investigate him, they found potential sources were too afraid to speak. State officials who disagreed with him were quickly dismissed.

After Modi became prime minister, he brought this authoritarian style to the entire country. The government barred thousands of nonprofits from raising money abroad, citing their supposedly unpatriotic activity. More journalists were pushed out, in part by owners who seemed afraid of crossing Modi.

When I first arrived at The Caravan’s offices, such pressure seemed distant. The staff were digging into all kinds of tough targets, including the mysterious death of the judge overseeing a murder case involving Modi’s top lieutenant. They did not seem to fear the consequences. When I asked Jose what kind of pieces he wanted me to work on, he smiled. “You should write something that will get you deported!” he said, loud enough that seemingly everyone could hear. (A colleague pulled me aside to assure me that I shouldn’t take the admonition seriously.)

But it quickly became clear that the magazine was under stress, particularly financial. In India, state-run companies take out large numbers of advertisements. So do businesses that are connected to the elite. As a result, outlets critical of Modi saw their advertising decline after he took power. That wasn’t always from direct pressure; “It’s a lot of self-censorship,” said Anant Nath, the owner of the magazine. Sometimes, however, there was a link. When The Caravan was working on a profile of the Modi government’s finance minister, Jose told me the advertising manager had trouble closing contracts with banks because the banks were getting calls about us from the finance ministry.

Advertising was not the only point of leverage. Indian authorities investigated independent media firms for allegedly violating tax laws. The government and its supporters repeatedly sued journalists. The Wire has racked up charges. The son of India’s national security adviser sued The Caravan for defamation. Jose is fending off 10 sedition cases.

The Caravan has run into other kinds of legal trouble, as well. While covering the aftermath of a Hindu nationalist riot, three of the magazine’s journalists were beaten by a mob. They reported the attack to the police. But rather than investigating the perpetrators, the police started investigating the journalists for inciting the violence.

Most of the people I know have been able to find well-intentioned lawyers who can represent them for reasonable fees. They were convinced that they would prevail in court. But the legal assault was still expensive and overwhelming. “The process becomes a punishment,” Nath told me.

For NDTV’s owners, it was punishment enough. After years of fighting against financial investigations, they sold the station to a billionaire who has long backed Modi. Most big outlets didn’t even risk an investigatory onslaught; they buckled preemptively. CNN-IBN, a cable station owned by India’s richest industrialist, forced out its top editor less than a year after Modi took office. “Editorial independence and integrity have been articles of faith in 26 years in journalism,” he said in his resignation statement. “Maybe I am too old now to change.”

Today, the Indian media’s coverage of Modi is mostly fawning. Everything good that happens in the country is, in some way, his achievement. His failures usually go undiscussed. The country’s main television news channels all resemble Fox, with anchors who constantly praise the country’s leader for his strength and smarts. They berate his critics as mendacious “anti-nationals” — people whose hate for India is boundless.

And yet Modi still has critics. That is, in no small part, because India still has independent outlets. Their survival is partially the result of luck. The country’s free press, for example, is generally owned by people without external, non-journalism business interests that could be a point of pressure for the government. Independent publications also usually have small readerships relative to the country’s main newspapers, and are thus less concerning to officials.

But their persistence is also the result of smart decisions by their owners and editors. Some outlets, for example, stay small even when they have the chance to grow, opting to save money rather than risk overextension. Publications have also learned how to cooperate to cover bigger stories. During India’s 2024 general elections, The Caravan, The Wire and an assortment of other outlets joined forces to report on the contest’s conduct and result. Two of the publications in that consortium, Newslaundry and The News Minute, have launched joint subscriptions to bring in more readers. Independent outlets also provide each other with legal support, including suing the government in response to censorship.

Yet the biggest thing these outlets have done to stay in business is get money from as many people as possible. For some of these outlets, that means putting up a paywall in hopes of massing subscribers. The Caravan, for example, launched a hard paywall in 2018, and its subscription count has since increased fivefold. As a result, it does not need many ads or rich benefactors to stay in business.

The News Minute put up a partial paywall in September 2023. But it has supplemented this income by deputizing its writers to fundraise for their reporting projects. If a writer wants to work on a particular story or topic, for instance, they put out calls to followers asking if anyone is willing to chip in. It has helped the outlet gain income from people who it would otherwise miss. “We realize that a lot of people don’t want subscriptions,” said Dhanya Rajendran, The News Minute’s editor-in-chief. “We have to give options.”

Not every independent outlet has a paywall. The Wire is free, instead relying on a wide base of donors. It makes for a difficult and precarious existence. “We’re out every month looking for money,” Chishti told me. But those donations have, thus far, been sufficient.

To be sure, none of these places is fully insulated from the government’s financial might. They could all use more advertising, and state pressure can make it hard to find clients. “With another government, a magazine like ours would be getting more advertisements,” Nath told me. These outlets could also use large donors, which are hard to attract. That is especially true after September 2022, when the government raided the Independent and Public-Spirited Media Foundation — a Bangalore-based organization that provides funding to journalism outlets — after it had given money to The Caravan and The Wire.

As a result, pay at these publications is low. Sometimes, it is infrequent. During my year at The Caravan, there were weeks where people didn’t receive their checks because there wasn’t enough cash. My $30,000 salary was among the highest there, and it was possible because it was entirely paid for by a U.S. foundation that was sponsoring me for a year.

Even so, I felt the squeeze. As the months went on, my bosses had me spend time writing grant proposals that could generate funding. I did so, in part, for my colleagues. But I also did it for myself. I wanted to stay after the year ended, and getting more money was essential to that task. Alas, the applications went nowhere. In July 2018, I flew back.

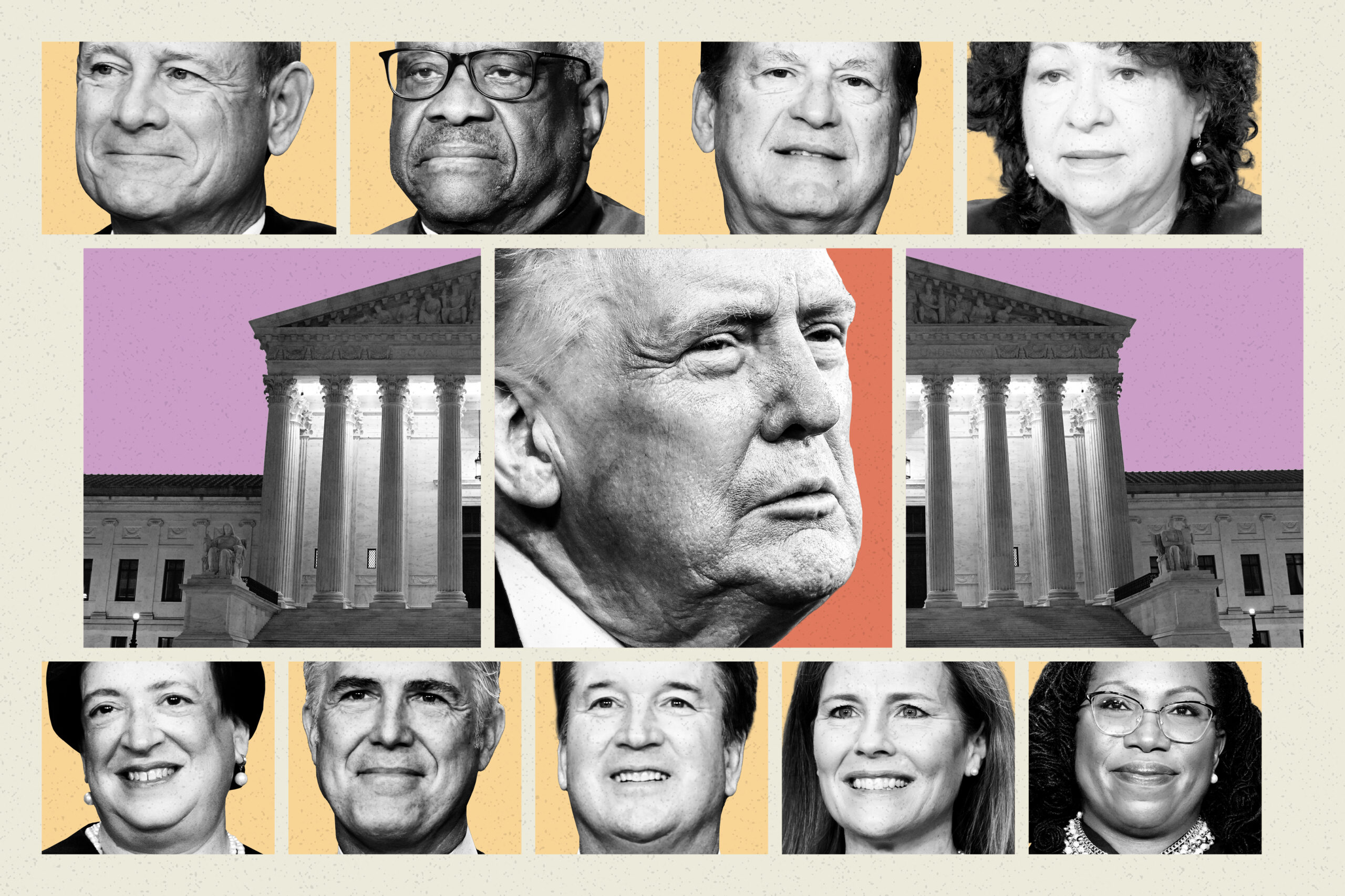

The state of American journalism is not as bad as that of India. For starters, there are still large, mainstream outlets that critique and investigate the president. But every one of them has come under intense pressure from the government. During his first term, for example, Trump threatened Washington Post owner Jeffrey Bezos’ main commercial enterprise — Amazon — in response to the paper’s dogged investigations into his government. The Trump administration has cut off state revenue to independent media, cancelling federal subscriptions to various publications. And the president has sued ABC, CBS, the New York Times, the Wall Street Journal and a host of other outlets.

Finally, and perhaps most concerningly, the administration has been investigating major media companies. Brendan Carr, Trump’s pugnacious Federal Communications Chair, has launched regulatory inquiries into ABC, NBC and CBS (but not Fox) for what he calls “biased and partisan conduct.” He has also been investigating NPR and PBS. Trump, for his part, successfully pushed Congress to cut $1.1 billion in funds for public broadcasting, creating headaches for the latter two outlets.

Unfortunately, Trump’s attacks have been effective. In addition to preemptively killing his paper’s endorsement of Democratic presidential nominee Kamala Harris, Bezos hired Will Lewis, a conservative journalist, to serve as chief executive officer of The Post. Lewis has since remade what was once a centrist opinions section into one that exclusively champions what Bezos calls “personal liberties and free markets.” Most legal experts believed that CBS and ABC (or their parent companies) were unlikely to lose to Trump in court. Yet both settled their lawsuits anyway, pledging millions of dollars to his presidential library. The former cancelled the Late Show, hosted by the liberal comedian Stephen Colbert. Its owner then sold the company to David Ellison, the son of a Trump-supporting billionaire, who hired a center-right journalist to serve as its top editor. ABC, meanwhile, temporarily pulled comedian Jimmy Kimmel’s show for comments he made after the assassination of conservative activist Charlie Kirk. Before the network did that, Carr had demanded that Kimmel be let go.

And yet some outlets remain unbowed. The New York Times’ newsroom, for example, has continued its investigations, and its opinions section maintains its center-left bent. Not surprisingly, its business model primarily depends on subscriptions, and its owner does not have outside business interests that can be pressured. NPR and PBS have stayed alive despite the federal cutoff thanks to a wide base of donors. And there are plenty of magazines and digital outlets that have avoided Trump’s onslaught.

Whether these places can all stay alive and independent as Trump’s attacks grind on is an open question. Only so many Americans are willing to pay for news; there is a reason why the industry was struggling before Trump took office. But my friends in Delhi are hopeful there will always be a market for good journalism, in India and the United States alike.

“I don’t think people actually like to live in an environment of dishonesty and misinformation,” said Puja Sen, The Caravan’s senior editor. “There are people who are looking for sober accounts.” Demand, in other words, would continue. Sen thought that supply would as well. The Caravan, after all, continues to get inundated with applicants for editorial jobs, despite the tough circumstances.

In fact, the tough circumstances may be why it remains such a desirable place to work. The same things that make being a journalist today dispiriting — the attacks on democratic institutions, the assault on the truth — provide endless fodder. They make the profession more essential and more fulfilling.

“In some sense, this is the best time to be a journalist,” Sen said. “You have so much to correct. You have so much material. You have so much to uncover.”