John Thune was going to miss his brother’s funeral.

Late on the last Thursday of January, the Senate schedule was crammed — a logjam of unorthodox nominees that needed to be confirmed to fill President Donald Trump’s cabinet, Democrats stalling and countering in the limited ways they could, the new president’s most vocal Republican supporters agitating for outright fealty and all but impossible speed. Thune, the new majority leader, had pledged to work weekends if needed, and this weekend was looking to be no different. His brother was dead — but he was prepared to have to put his job first. Then, though, and somewhat unexpectedly, Thune and top Democrat Chuck Schumer agreed to punt the tasks at hand to the week to come. That night, the Senate adjourned just before 8, and quietly, privately — unreported, in fact, until now — Thune the following morning got on a flight to California.

He still didn’t arrive in time for the graveside service Friday afternoon, but that evening, at a gathering at the Irvine-area home of one of his nieces, Thune listened to a group of close family share memories of his older brother — the first of his four siblings to die. And he talked, too, about an idea he once had encountered in a book — the difference between “resume virtues” and “eulogy virtues,” his younger brother told me. “John said,” Tim Thune said, “‘We build our lives worrying about our resume, and promoting self, and what does that look like?’ He said, ‘At the end of the day, when you’re gone, what are people going to say? How will you be remembered?’”

It’s not hard to see how these days this might be on his mind. Thune is the leader of the Republican conference and of the upper chamber of Congress, which if anything undersells the significance of his post — because what he is, actually, is the most important person in one of the most important institutions at one of the most important moments in the modern annals of the American experiment.

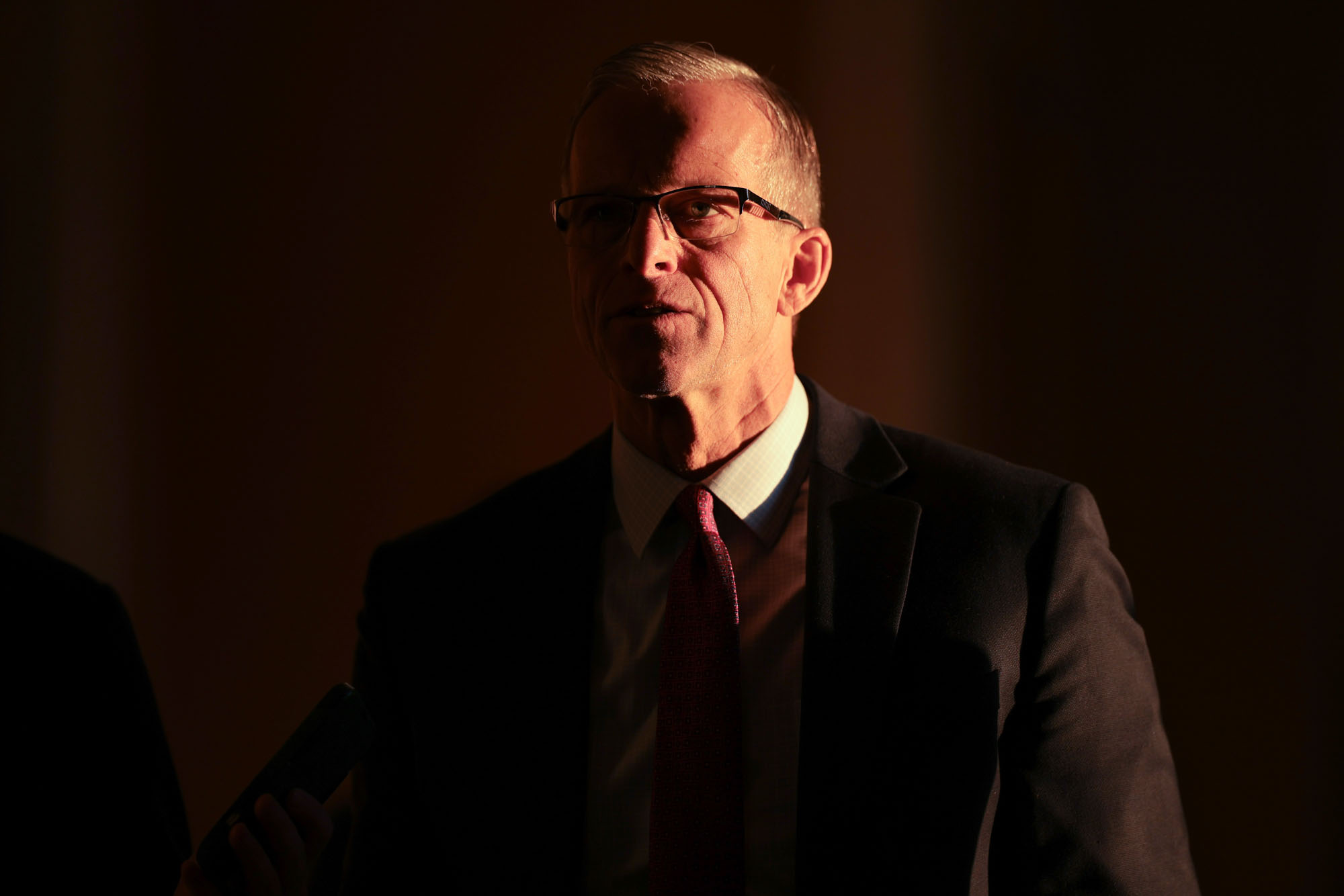

Also, though, after nearly 30 years on Capitol Hill, the 64-year-old son of small-town South Dakota just as pointedly is at odds with the time and its trends. He is devout but not proselytizing, by all accounts measured, affable and steady — a father of two daughters, a husband of more than 40 years. He’s unambiguously conservative but temperamentally moderate — a collaborator instead of a combatant, even-keeled and deliberative when so much of the populace seems to want intemperate attacks. In a move-fast-and-break-things era of anti-government ardor, he’s virtually a public-sector lifer, an easy-does-it institutionalist. The subject of nary a scandal and scant few lengthy profiles for somebody of his stature, John Randolph Thune — by upbringing, experience and disposition — is the utter antithesis of Donald John Trump. Thune has said in the past he did not want Trump to be the nominee of his party, let alone its overlord, let alone the president. Now he needs to decide on a relentless basis how to work with a reelected, reemboldened Trump. Thune finally got to where he wanted to get. He’s at his professional apex. Turns out it’s a personal crossroads.

Aides, allies and friends in Washington, South Dakota and around the country speak about Thune with an uncommon unanimity and conviction. “A man of integrity,” Larry Rhoden, the governor of his home state, told me. “One of the most earnest, humble, decent people I’ve ever known,” longtime Thune consultant Scott Howell told me. And as leader, they say, he’s so far doing notably and remarkably well. “John’s doing a good job — a great job,” Thom Tillis, the senator from North Carolina, told me. “He’s producing,” Mike Rounds, his fellow senator from South Dakota, told me. “He’s at peak performance,” Steve Daines, the senior senator from Montana and Thune confidant, told me. “He’s batting 1.000.” Even his GOP skeptics grant that for now they are pleased — maximum alignment, minimal pushback, and the most challenging nominees, from Pete Hegseth and Tulsi Gabbard to Robert F. Kennedy Jr. and Kash Patel, every one of them duly confirmed. As one Trump- and MAGA-oriented operative put it when I asked for his take on Thune: “I expected less.”

There is, however, a not inconsiderable camp of Democrats and anti-Trump Republicans who expected more. “To the extent that there needs to be Republicans in the Senate, and obviously there’s going to be, I wish they were all like John Thune,” Drey Samuelson, the longtime chief of staff of the late Tim Johnson, the last Senate Democrat from South Dakota, told me. “I mean, I don’t know anybody that really doesn’t like John Thune,” Samuelson said. “I like him.” For people such as Samuelson, people who for years have appreciated the man even while disagreeing with the policies he prefers, it’s what Thune is not doing and not saying that’s the source of their increasing alarm and chagrin. The Senate, after all, is constitutionally obligated not simply to be a legislative partner of a president but a check on ominous partisan passions and executive overreach. It is in this respect up to Thune to see and know and hold the line. “I think he respects and admires the separation of powers,” Ted Muenster, a chief of staff to former South Dakota Democratic Gov. Richard Kneip, told me, “and I think Trump has an endless desire to have power, and he’s very likely to run into a situation where he assaults the fundamental constitutional role of the Senate, and I think Thune is likely to draw a line in the sand.”

Those who know Thune well say he will know where that line is, and when it’s crossed. Samuelson, Muenster and many others like them, though, are waiting with growing angst. In response to Trump’s pardoning of more than 1,500 Jan. 6 convicts, his signing of an unprecedented onslaught of executive orders, his unleashing of Elon Musk and his pell-mell minions on the civil service and his persistent stretching and testing of the constitutional constraints on the powers that he has with the freezing of federal aid, the firing of federal workers and the slashing and shuttering of federal agencies, Thune publicly has been mostly mum — questioning here and there but generally signaling at least partial or tacit consent.

“He’s going to have to pick,” Steve Jarding, a seasoned Democratic operative with roots in South Dakota, told me. “If I’m John Thune, OK, I want the title — but I want a legacy,” he said. “And I don’t want my legacy to be that I was a bootlicker for Donald Trump.”

“I would hope there’s a little inner turmoil,” Mark Salter, a longtime adviser to the late John McCain, told me. “You are watching the executive branch usurp all the power and authorities given Congress under Article I,” Salter said. “Maybe he thinks, ‘I’ll preserve my influence, and down the road, when something worse comes along, I’ll be able to stop him from doing it’ — but it’s going to get harder to oppose him, not easier.”

In California, Thune that Saturday attended the memorial service for his brother. He didn’t speak, but he heard his brother’s friends describe him as a selfless servant, a gifted listener, a high school teacher who was in his community in some sense something like a minister — somebody who had lived a life, in the words of one of his nieces, “guided by principles he believed in.”

A couple of hours later, Thune boarded a charter flight with his younger brother. Up in the air, on the way to Sioux Falls for a stopover in South Dakota before heading back to the cauldron and crucible of Washington, he brought it up again — the idea he had encountered in a 2015 book by New York Times columnist and PBS political commentator David Brooks. “The resume virtues are the ones you list on your resume, the skills that you bring to the job market and that contribute to external success,” Brooks wrote in The Road to Character. “The eulogy virtues are deeper. They’re the virtues that get talked about at your funeral, the ones that exist at the core of your being.”

“What are you doing for eternity?” Tim Thune told me. “I think,” he said, “that’s always on his mind.”

“Everybody has that voice in their head,” John Thune once told a reporter from the Rapid City Journal. He was talking about his father. “He’s kind of that voice inside my head,” he said, “the one that knows where the lines and the boundaries are.”

Harold Thune was born in Mitchell, South Dakota, on Dec. 28, 1919. The son of an immigrant from Norway — Nikolai Gjelsvik became Nick Thune when he arrived at Ellis Island in 1906 — he grew up on the high plains in Murdo, a small, sparse, windswept spot in which earlier settlers had sought shelter in huts made of sod. He was a basketball standout, first leading Murdo to the state championship game, then becoming at the University of Minnesota the most valuable player on the team. At a Minneapolis soda shop he met a Canadian-born clerk who’d lost her railroad-worker father in accident when she was not yet 3. Harold Thune and Yvonne Patricia Bodine got married after he’d enlisted in the Navy after Pearl Harbor, and he was sent to the Pacific after that. He flew more than 60 missions off the USS Intrepid. In his Grumman Hellcat he downed four Japanese Mitsubishi “Zeros” and was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross. “You always wanted to keep the enemy off your tail,” he once said. The Japanese military’s “‘Zero’ was a lighter plane and could outturn the planes that we flew.” One way to win a fight, he learned, was to rely on experience and nerve. Another way, he came to believe, was to try to not have one in the first place.

After the war, he moved home to Murdo, population less than 1,000. Even Main Street was “gumbo” — hard in the winters’ sub-zero cold, a slurry of mud when the snow and ice melted. It was, thought his wife, “the end of civilization.” But isolation bred connection. People, it was apparent to the people who lived there, needed each other — even people who sometimes didn’t necessarily even like each other. People had to work with what they had and who was there. They had to stop and think before burning a bridge.

The Thunes lived at 311 Jackson Ave. It was 800 or so square feet with a living room and two bedrooms and a kind of a third behind a curtain by the kitchen. The only bathroom had a toilet, a sink and a stool. The only shower was in the basement with marginal heat. They had five kids.

Bob was born in 1946 and Karen in 1947 and Rich in 1949. John was born 12 years later in 1961. “We don’t understand what God is doing here,” said their mother, “but He makes no mistakes.” Tim was born in 1964. John Thune was a middle child who was also a big brother.

In school, where his mother was a librarian and his father taught history, math and international relations, coached football, basketball and track and was a bus driver and the athletics director who helped build the gym, Thune seemed to do everything, too. He sang in the glee club and the swing choir. He played the tuba in the band and was a detective in the play. He was an attendant on the homecoming court, he emceed pep rallies, and he took second in oratory at state debate. He was in the National Honor Society and always on the honor roll. “He wouldn’t have dared not be,” Margie Peters, his English teacher, told me. “His family expected it,” she said. “He always did his work.”

In sports, Thune was the quarterback on the football team, ran a fast half-mile and mile on the track team, and at 6-foot-4 was the basketball team’s high scorer and first-team all-state as a senior — and always, according to schoolmates, classmates and friends, a natural but curious sort of leader. “Everybody kind of looked up to him, but he wasn’t a commanding leader. He just kind of worked through everybody else,” Greg Glaze, one of his Murdo basketball teammates, told me. “If that makes any sense,” he said. “So he’s not telling you what to do?” I said. “No,” Glaze said. “He’s working with everybody. He’s doing what they need.”

On many mornings Thune’s mother sang in the house in her soprano. The sun is a-rising to welcome the day. High-ho! Come to the fair! “She had a way,” Thune would say, in the Murdo Coyote newspaper, “of making you like the day, whether you wanted to or not.” She had her kids read, even in the summer, an hour every day. She saw to it that they took piano lessons before school. Thune’s father saw to it that they did the lessons right. He sat with them to make sure. His father, Thune once said, didn’t like “ball hogs.” He didn’t like people who prized “personal glory.” The best members of a team, his father stressed, did what they did for “the good of the team.” The best members of a team, he believed, made the other members better.

Thune as a basketball star missed the last shot he took. It was the end of a one-point loss to the archrival in the championship of the district. “It wasn’t like it was a cupcake shot. It was a long ways away,” Brian O’Reilly, one of his teammates, told me. “Everybody in the gym knew John was going to get the ball, and of course they double- and triple-teamed him, and he tried his best,” Chris Venard, another one of his teammates, told me. “I don’t think anybody blamed him,” he said. “He blamed himself.” He sat alone in the locker room until his coach and his mentor tapped him on the shoulder. “John,” Jerry Applebee said, “it’s time to get on the bus.”

The motto of Jones County High School’s Class of 1979: “Today, we follow; tomorrow, we lead.”

“John has always wanted to serve and to do what’s right,” his father once told a reporter. “He told me if the hard thing is the right thing to do,” he said, “he’ll do the hard thing.”

He conceded.

The real beginning of Thune’s long electoral career could have been the end. He was already better than a decade deep in his political life. From the mid-’80s to the mid-’90s, he’d been an eager aide to Republican Sen. James Abdnor, a special assistant for the U.S. Small Business Administration, the executive director for the South Dakota Republican Party and the South Dakota Municipal League, the state railroad director.

In 1996, he’d run for Congress and won. “There’s an old saying that organizational change comes from gentle pressure relentlessly applied,” he told NPR. “You do things incrementally. And you do it in a fashion that promotes,” he said, “a spirit of cooperation, and that’s really the only way you can get things accomplished.”

And in 2002, in his third term in Congress, he’d thought about running for governor, but President George W. Bush helped sell him on a run for the Senate — a potential pivotal vote in an evenly cleaved chamber. But in the end, he’d lost to Tim Johnson, the incumbent Democrat — by 524 votes. Some whispered of rumors of fraud on the Native American reservations in the state. Thune spurned calls to challenge the results. He did not, he said, want to put South Dakota “through a lengthy recount which would not guarantee my victory or fix any irregularities” and “would be painful for the state and unlikely to change the outcome.”

“He competes. I mean, he competes,” Karl Adam, a lobbyist in Pierre who’s a longtime Thune friend, told me. “But John’s not a disruptor.”

Also, though, Thune “set himself up” for a run to come, Fox News’ Michael Barone said at the time, “by not being a poor loser.”

And so two years later, he decided to run again — this time, though, against Tom Daschle, the Senate minority leader who had been the Senate majority leader, the top Democrat in Washington. It was seen as a very tall task, and at stake was his political career — lose for the Senate for the second time in three years and he was probably done. But it was “a race that needed to be run,” Thune said at the time. “He just felt,” Dick Wadhams, his campaign manager, told me, “it was the right thing to do.”

Bush was running against John Kerry for president, but the New York Times dubbed Thune-Daschle “the other big race of 2004.” The thrust of Thune’s case: After 26 years in Congress, Daschle had lost touch with South Dakota and become too Washington-enmeshed. “There is negativity and partisanship going on in Washington, and Daschle has become a symbol of why things don’t get done,” Thune said in a fundraising letter. “I’m proud to be a member of my party,” he said in an ad, pitching himself as a more independent option. “But … no party is right all the time.”

Daschle countered by saying Thune had had a chance to oppose Bush a couple years before during a flap about a dearth of federal drought relief for South Dakota. In a debate on NBC’s Meet the Press, host Tim Russert asked Thune why he hadn’t more forcefully called that out. He had, Thune replied, shared his concerns — in private. Daschle suggested that wasn’t enough. “John’s a follower, and I think there’s something to be said for following, but you’ve got to be more than a follower in the United States Senate,” Daschle said.

Thune won. He beat Daschle by 4,508 votes — a little more than a percentage point — the first time in 52 years a sitting Senate leader had lost. It marked a lasting shift in the political makeup of South Dakota — a resolutely conservative state that throughout the latter half of the 20th century nonetheless had sent its fair share of Democrats to Congress. Not anymore. “That was kind of it for the Democrats in South Dakota,” Tony Venhuizen, the current lieutenant governor, told me. Time magazine labeled Thune a “Giant Killer,” and the Sunday after the election, he was on ABC’s “This Week” as the Republican counterpart to the Democrats’ new leading light — Senator-elect Barack Obama.

In Washington, in his first term in the Senate, Thune carried on with an approach he’d established in his six years in the House, according to staffers, allies and watchers of Congress from both parties. He scheduled with fellow members dinners or Bible studies. He had an uncanny capacity to remember names — aides, colleagues, spouses and kids. He was known as a good boss, conspicuously minimal churn on his staff, people who worked for him often working for him for an unusually long time. He was reliably ready in the halls of the Hill to banter with reporters to make and maintain rapport. He listened more than he spoke. He waited and he watched. Seldom was he a first mover. “He’s a skilled hunter,” Kyle Downey, his top communications adviser early in his Senate tenure, told me, “so he’d often say, ‘Let’s just keep our powder dry.’”

In 2008, he not only endorsed John McCain for president but campaigned for him. There was more than political admiration. There was something of a personal connection. His father had received his Distinguished Flying Cross Award from McCain’s grandfather. And Thune was on the list for the vice-presidential nod — the one that went instead to Sarah Palin. In 2010, he was reelected without opposition. And he thought hard about running for president heading toward 2012. “If he wins the nomination, it will be because he is an exceptionally skilled retail politician who can communicate a kind of midwestern, common sense conservatism that is ascendant in reaction to liberal profligacy,” Stephen F. Hayes wrote in The Weekly Standard. Mitch McConnell was a fan. “I think he’s the complete package and is the kind of person who could conceivably go the distance in a race for the presidency,” McConnell, then the Senate minority leader, told Hayes. The GOP field was open. Obama, seeking his second term, seemed vulnerable.

But Thune decided against a White House run. His mother neared the end, a decade of dementia having taken its toll. “She would sit down at a meal, and she would say, ‘We suffer greatly here on Planet Earth,’” Tim Thune told me. “She might say that 30 times over the next 15 minutes.” She died at 90 in March of 2012. “The last time I saw her,” her senator son wrote the following week in the Murdo Coyote, “she was already laboring heavily, but when I asked her how she was doing, she said, ‘Great.’” Two months later it was James Abdnor. Thune gave the eulogy. “Jim Abdnor,” he said, “reminded us that it’s not about personal ambition but about the common good, that you can have a title but that doesn’t determine your value, and that you can make a difference without compromising who you are.” Endorsing Mitt Romney — “on Day One of Mitt Romney’s presidency,” Thune said of the GOP nominee, “the transformation of Washington will begin” — he refocused on the prospect of Senate leadership.

He had been the chair of the Senate Republican Policy Committee from 2009 to 2011. He had been elected by his colleagues to be the conference chair in 2012. Under the tutelage of McConnell, Thune was going to climb the ladder on the inside, patiently biding his time, steadily waiting his turn, responsibly plotting his ascent.

And then down the escalator came Trump.

Thune at first didn’t think much of Trump’s run. He didn’t think it would last. “A short-term phenomenon,” he said that summer of 2015. “He’s someone who grabs attention,” he said, “but does he have the potential to go the distance?”

As Trump, though, started to surge, Thune started to shift — even if the shift was slight. “There is no denying that Donald Trump has struck a chord with voters throughout the country,” he said. “It has been the summer of Trump for sure,” he said. “But,” he said, “I think there will be other people who will emerge.”

They did not. And by December, when Trump floated the notion of banning Muslims from entry into the country, National Journal asked the question: Is there a line Trump can’t cross with Republicans? Thune in effect was inclined to leave it to the voters. Trump’s comments about Muslims were “not consistent with the values and beliefs that we hold as a nation,” he said. “I think in the end,” he also said, “we will nominate a candidate that can lead our party in the general election.”

That, in 2016, is what happened — just not how Thune thought it would. He didn’t go to the Republican National Convention. He spoke up when Trump attacked Gold Star parents who spoke out against Trump at the Democratic National Convention. “Donald Trump,” Thune said, “has to develop a thicker skin, realize that these campaigns and elections are not about him. It’s about the future of this country.”

And in early October, in the wake of the shock of the Access Hollywood tape, Thune was the seniormost Republican to finally in essence answer that National Journal question. Here was the line. Trump, he thought, should leave the race — “should withdraw,” Thune said in a tweet, “and Mike Pence should be our nominee effective immediately.” Thune said the recording was “more offensive than anything I’ve ever seen.” But even this answer came with a clause: If, he said, the top-of-the-ticket GOP option remained Trump, Thune would vote for Trump.

So he did, and so, of course, did nearly 63 million others, and so in 2017 Thune established a certain template to the way he dealt with and talked about Trump. Trump’s baseless insistence that he’d won the popular vote and desire for an investigation into fraud? Thune “had not seen any evidence” of that, but “we’ve moved on,” he said in January. Trump’s eye-opening and unsubstantiated charge that former President Barack Obama had wiretapped Trump Tower? “Boy, I have no idea,” Thune told POLITICO in March. Trump’s quest to quash Obamacare? “We are proceeding according to plan,” Thune said in May. “But,” he said, “less drama on the other end of Pennsylvania Avenue would be a good thing.” And so it went — Thune backing Trump in his health care-repeal and tax-cut initiatives while lamenting his inveterate feud-picking and wanly wishing he would stop tweeting, eventually settling on a sort of Pavlovian posture that was pragmatic, or acquiescent, or both. The man from Murdo didn’t not push back against the man from Manhattan — he just didn’t call him out. Thune was no sycophant — nor, though, was he some stance-taking crusader.

Thune’s M.O. was a dependable level of trying to find the thinnest of middle grounds that some found measured and others found milquetoast. It wasn’t always outright equivocation. But it was also never downright condemnation. Once at a concession stand at a basketball game in South Dakota a man told him he wasn’t sufficiently pro-Trump and he turned around and another man said he wasn’t suitably anti-Trump. “I know a lot of people are unhappy with him, and they vent a lot to me on a regular basis, too, but what they have to understand is he was elected by a big majority in South Dakota,” Thune said that summer at the Brown County Fair. “To me,” he told a reporter from the Aberdeen American News, “it’s about being a realist, and to be a realist about my work. I know what it takes to get things done in Congress, and I know that it takes a president to sign legislation into law, and we’ve got to be able to function together to do that.”

In 2018, it was more of the same: Thune “conveyed” “concerns,” he discussed what was “helpful” and “productive” and what was not, he hoped people would be “respectful.” In the spring, a White House staffer made an off-color joke about the dying, cancer-stricken John McCain. Thune was not pleased. Everyone involved should have apologized, he said, but he also employed a familiar phrase. It was “time,” he said, “for everyone to move on.” In late August, just two days after Thune on the Senate floor eulogized McCain — “he reminded me and all of us every day that life is not about advancing ourselves but about serving a greater cause, and that, paradoxically, it is in service that we find freedom” — a former California pastor who once was a close colleague of Thune’s oldest brother posted on his blog an open letter to Thune. “I am unable to contain my disappointment,” Ken Kemp wrote, criticizing Thune for staying “conspicuously silent” in the face of what he considered Trump’s mounting transgressions. “Knowing something of your heritage, I must believe that you are better than this,” Kemp wrote. “Will you, in the tradition of biblical prophets, find the audacity to speak truth to power?” To Kemp’s surprise, he heard back from Thune, who sent Kemp a handwritten note. “You obviously put a lot of thought into your letter and I appreciate your honesty,” Thune wrote. “It clearly comes from a place of strong conviction. This,” Thune said, “is a very challenging time to be in public life.”

That didn’t change in 2019, and neither, really, did Thune — now the GOP whip. “I wish he wouldn’t tweet as much,” he said in January. “There are concerns, and our members are conveying those,” he said in February. “A bridge too far,” Thune said in March of Trump’s proposal to declare a national emergency to get money to build more border wall. He tried to get Trump to back off of tariffs. He expressed disapproval of Trump’s conduct that led to his first impeachment but also the Democrat-led impeachment itself. He voted to acquit. “There is a real concern out there that the behavior of the president … obviously isn’t what some of our members would condone, but at the same time it didn’t reach that threshold that would allow him to be removed from office,” he said on the PBS NewsHour. But was what the president did, he was asked, wrong? “At this point,” Thune said, “it’s kind of a discussion that is past us.”

And as the first Trump administration careened toward its chaotic conclusion — the pandemic, the murder of George Floyd and the fallout, the president’s increasingly manic comportment — Thune urged him to listen to health professionals and to strike a tone that was more “calm,” more “reassuring,” more “empathetic.” When Trump wouldn’t commit to a peaceful transition of power? Thune said that couldn’t happen. “Republicans believe in the rule of law,” he said in September. “We believe in the Constitution.” And in November, after Trump lost, Thune balked at helping him challenge the certification of his defeat. “It’s just not going anywhere,” he said. “I mean, in the Senate, it would go down like a shot dog.” Trump responded on Twitter as if Thune were a declared enemy: “He will be primaried in 2022, political career over!!!” Trump said — at which point Thune shifted some. “We are letting people vote their conscience,” he told reporters at the Capitol. “This is an issue that’s incredibly consequential, incredibly rare historically and very precedent-setting,” he said. But then Jan. 6, 2021, happened. It seemed for a moment that Trump indeed was done and done for good, and Thune, in turn, seemed to rediscover his resolve.

“Today,” Thune said on Jan. 6, “has been a sad day for America. The violent behavior at the Capitol is inexcusable and disgusting, but we won’t be deterred from our Constitutional duty. We need to work together to protect our democracy. Please pray for our country.”

“Our identity for the past several years now has been built around an individual. You got to get back to where it’s built around a set of ideals and principles and policies,” he said. “I think people — including the president and others around him and other voices and in media circles and social-media platforms — have been putting out false facts and then getting people to believe those things now for weeks,” he said, “and it’s just time for it to stop.”

And yet in the subsequent and second impeachment Thune voted again to acquit. “What former President Trump did to undermine faith in our election system and disrupt the peaceful transfer of power is inexcusable,” he said. But impeachment, Thune explained, was meant for removal from office, and Trump was already out of office, and impeaching him after his ouster, he argued, would take the power out of the hands of the voters.

It had been a long four years. “There was just kind of a shift in 2016 where everything just kind of changed,” a former Thune staffer told me. “Just all the things … got harder.” Thune thought hard about not running for reelection in 2022. One reason was the chance to spend more time with his wife, his daughters and his grandkids — but another was Trump, the durability of his political viability, the looming possibility or even probability of his return.

He made his choice. He ran again.

“He saw,” Mike Rounds, his fellow senator from South Dakota, told me, “there was a possibility of becoming the leader …”

How long had Thune wanted to be leader?

“I think,” Rounds said, “he’s wanted to be a leader since he got here.”

But he wanted to be the Senate majority leader working with a Republican president who wasn’t Donald Trump. In the 2024 primary — after Rounds did the same — Thune endorsed Tim Scott.

But Trump won the South Carolina primary on Feb. 24 and with it for all intents and purposes the GOP nomination. Thune called him that night. He endorsed him the next day. And he announced his candidacy for leader a week later. He made a trip to Mar-a-Lago shortly thereafter. He said he’d worked with him before. He said he could work with him again.

“We’re more animated these days by the personality of Donald Trump, and that’s the reality we live with and deal with if you want to be involved in public life,” Thune said after he announced his bid to succeed McConnell. “That’s kind of where our voters are,” he said. “And you have to listen to your voters.”

“God wants us to be out there being salt and light in the culture,” he said when he won. “I want to be a hopeful, optimistic leader,” he said, “a leader who’s willing to do hard things, make hard decisions.”

The fire in the fireplace in the office of the leader on the Senate side of the Capitol was smoking. The eyes of the wall-mounted head of a bison named Murdo were watching. The other day, toward the tail end of 10 straight weeks of the Senate in session, going on two months into the second Trump term and with the specter of a government shutdown in the air, the trim Thune wore a blue suit and sat down to talk.

I asked him about that voice in his head of his dad. The one that knows where the lines and the boundaries are. “People I’ve talked to, Democrats, too, admire you for knowing where the line is,” I said. “Where in this moment,” I asked, “is that line?”

“Well,” he said, “I mean, I think that you have to pick and choose your battles. And obviously right now I think this is an adjustment phase that we’re in. We’ve got an administration that’s incredibly aggressive, that’s moving quickly and decisively, and to the Democrats’ displeasure — in their view, too quickly, too decisively — but I think at the end of the day it’s defending the prerogatives of the institution. I mean, I think the Senate, as an institution and the Article I branch of the government, constitutionally has a role to play, and I think it’s important that the leader understand and be willing to defend the institution and preserve its unique role in our democracy …”

“In what ways in the last two months,” I said, “have you as leader defended the prerogatives of the institution?”

“A willingness to adhere to the rules. Everything we’ve done so far with regard to nominees, notwithstanding a lot of pressure to break the rules and do things differently and all kind of recess appointments — there are lots of ideas being thrown around out there — we’ve done it the old-fashioned way, and we have just ground things out, pounded away at getting the job done. And I think there’s always a lot of pressure from — and there was in the first time around, in the first Trump term, to get rid of the filibuster — and we resist that because we understand the unique role that the founders had for the Senate,” Thune said. “There are constantly threats to and efforts to undermine the Senate’s role.”

“Have you,” I said, “said to the president at any point, That’s our job, not yours?”

“I don’t know if I’ve said it exactly that way,” Thune said with a laugh. “It might’ve been a little bit more diplomatic …”

“But you’ve said a version of that, privately, diplomatically?”

“Or when asked by people — whether it’s the president or people around him or people who share some of his views on how we should do things around here — I think,” Thune said, “I’ve been very clear.”

People who know him well these days sometimes watch him and worry about the toll this job is taking. The people who raised him are gone. His mother and Abdnor died in 2012. His father died, at 100 years old, in 2020. Coach Jerry Applebee died just this January. Now his older brother. “My prayer for him,” his younger brother Tim told me, “is don’t let Washington corrupt you. You’re John Thune. You’re the kid from Murdo. Stay the kid from Murdo. Don’t let Washington corrupt you.”

He has to this point as leader of the Senate in this country’s 119th Congress compiled a record of what some see as accomplishment and what others consider accommodation. He toasted Trump at his inauguration. “We’re not looking backwards, we’re looking forward,” he said of the Jan. 6 pardons. “This is not unusual for an administration to pause funding,” he said of the aid freeze. “The president is somebody who sees great value in the use of tariffs as a tool, and we’ll have, I’m sure, lots of conversations,” Thune said of Trump’s tariffs that could have massive consequences for among many others his own farming constituents in South Dakota. He’s “put some ideas out there,” he said of Trump’s musing about taking over Gaza and making it a seaside resort. “Anything that DOGE does will be factored into what we do here,” he said of the activities of Elon Musk. “The American people handed him a decisive mandate,” he said. “It’s important we honor that mandate by confirming his nominees as quickly as possible,” he said. He’s praised Trump’s picks for his Cabinet. “We’re trending in the right direction,” he said. And in the aftermath of the Oval Office blowup between Trump, Vice President JD Vance and Ukraine President Volodymyr Zelenskyy, even as some fellow Senate Republicans reacted with great consternation — “I am sick to my stomach as the administration appears to be walking away from our allies and embracing Putin, a threat to democracy and U.S. values,” said Alaska Sen. Lisa Murkowski — Thune did what he does. “No question in my mind that Russia is the aggressor,” he told South Dakota’s Mitchell Republic. But he didn’t clearly criticize the interaction or Trump’s part, calling the meeting “spirited” and pointing to the future. “Obviously,” he said, “there will have to be some subsequent follow-up meetings that occur, but hopefully they got some of that out of their system …” Thune aides say his relationship with Trump has never been better.

“Talk about the right person being in the right place at the right time,” Scott Howell, the longtime Thune consultant, told me. “The years of his service have culminated in this moment,” Steve Daines, the Montana senator and Thune confidant, told me. “He’s smart enough,” Larry Rhoden, the South Dakota governor, told me, “to get behind Trump, lock, stock and barrel,”

But Thune’s role, which is to say the role of the Senate, is not exclusively or even primarily to work with the president and enact the agenda of the executive, according to his critics. The Senate, in the words of James Madison, is supposed to “protect the people against the transient impressions in which they themselves might be led.” The Senate, in the words of Mike Mansfield, history’s longest-serving Senate majority leader, is “one of the foundations of the Constitution” — “one of the rocks of the Republic.”

And the current majority leader? “You are in an extraordinary position now to curb this presidency and keep it in bounds,” Ken Kemp said this month in his latest open letter to Thune. “I was trying to appeal to the better angels of his nature, because they’re there,” Kemp told me. “I’ve been waiting to see you take your stand,” Kemp wrote. “I’m still waiting and hoping.”

“The next year or two will tell a lot about what matters to him and how much it matters,” longtime Tom Daschle adviser Pete Stavrianos told me. “On one side you have his ambition, and on the other side you have what he believes in about our system, and democracy and the prerogatives of the Senate,” he said. “My guess he’s at least somewhat tortured on the inside.”

“It’s not an overstatement, it really isn’t, to say the fate of our democracy and our country may be determined by a single decision that he makes,” Drey Samuelson, the former Tim Johnson chief of staff, told me.

“It’s a damn shame,” Mark Salter, the longtime John McCain adviser, told me. “God,” he said. “It’s just not worth it. Your time is so finite. It’s so brief. Your life is brief. But your time in public life is briefer. And when you’re gone,” he said, “you’re gone.”

This week in his office Thune brought up David Brooks without me having to ask. “David Brooks talks about resume virtues and eulogy virtues,” he told me. “I went to my brother’s funeral in California here not long ago,” he said. “I was reminded of the importance of eulogy virtues.”

In what ways, I wondered, is what he’s doing right now and how he’s doing it “resume” work, and in what ways is it “eulogy” work?

“I think sometimes what you do might be considered resume work,” he said. “I think how you do it is considered more eulogy work.”

“You listened to what people said about your brother,” I said to Thune. “What do you think people will say about you at your service?”

“Well,” he said, “that chapter’s probably still being written.”

“What do you think they will say about this particular moment in time, this role that you’re playing right now?”

“Well,” Thune said, “I think people understand that it’s not an easy job. I mean, you’re working with a really big personality who has a distinct way of doing things, which kind of keeps you on the edge of your seat. And you have to be adaptable. You have to be somebody who plays the long game and realizes that you do live your life in 24-hour compartments — it’s a day-to-day thing — but you try and keep in perspective the long game. And so every day that we get up and do the work here you understand that you’re trying to bend the trajectory of what you’re doing in the direction of freedom, preserving democracy and making the world and this country a better place.”

“Do you think you’re succeeding?” I asked.

He laughed a little.

“The chapter,” Thune said again, “is still being written.”